#71 Good process is evolved, not designed

Lessons in creating process, reducing friction and adding secret sauce

One story about RIP Medical Debt in Subbu’s weekly email caught my attention:

RIP buys the debts just like any other collection company would — except instead of trying to profit, they send out notices to consumers saying that their debt has been cleared. To date, RIP has purchased $6.7 billion in unpaid debt and relieved 3.6 million people of debt. The group says retiring $100 in debt costs an average of $1.

Such a novel solution - built around the existing shortcomings of our systems, by the folks who were able to understand it from within.

I’ve had a busy week at work & at home. And I expect it to be the same in the coming month or so. Let’s see how to keep up the momentum.

For now, let’s get to today’s finds.

1. Friction-killing tactics to make products more seamless

When it comes to consumer products, Kintan Brahmbhatt has a very simple definition for Friction - anything that gets in the way of a customer and a task. Put another way, it’s any obstacle that prevents a user from trying or using a product or service. His firstround post is a good read around “Friction-killing tactics to make products more seamless”.

He talks of 3 types of friction:

He then talks about how to detect and anticipate points of friction. There are multiple suggestions around how to reduce it. His examples from his Amazon journey are fairly relatable and makes the discussion easy to understand. One surprising message - not all friction is bad. Some of it may be good for the customers & you. How you mask it well is the key in creating the right experience for the user.

2. Good process is evolved, not designed

Will Larson’s blog Irrational Exuberance has an interesting mix of posts around working & managing teams in new age orgs. I’ve read a few and have not subscribed to his newsletter.

In “Good process is evolved, not designed”, he starts on this premise:

When we talk about creating a process, we almost always say that we designed a process. Design is a great word, because it implies the kind of careful thoughtfulness that great process does indeed possess. However, it’s also a misleading word, because great process never emerges from the Feynman algorithm (“write down the problem, think very hard, write down the solution”), but instead derives from guided evolution.

He goes on to talk about how to evolve a process. One step that really stood out for me:

2. Look for alternatives. Process is so expensive to maintain that we want to start out spending some time trying to avoid creating a new process. It’s quite possible that the problem statement is really feedback to improve your existing processes, not evidence that you need a new policy. If you can identify an existing process to improve instead of creating a new process, generally prefer to do so.

He has done a fair bit of writing around hiring as well. You can check this out for his latest covering some popular ways to improve hiring quality.

3. SEO 101

Over the last month, I spoke to a bunch of folks to learn more about SEO. It seems like a straightforward thing - the ground rules are simple & known to everyone. And so, the real magic is in the execution. And patience, of course.

If you’re interested in catching up on the basics, this tweet from Karthik Sridharan does a fairly good job. He offers a free course on the topic as well.

4. The Secret Sauce

Dan Lewis’s “Now I Know” is one of my favorite newsletter to find something interesting. He covers stories from diverse topics and has a beautiful way of narrating them.

This Friday he had a special segment covering what he called “the secret sauce”. His story was about the fanatic pace at which Wikipedia entries for Queen Elizabeth II were updated post her death. But, I’m not sharing it for that. He spoke about why it happened the way it happened and what keeps a product (or movement) like Wikipedia going.

Here’s his core message - .

As I said, MavsWiki didn’t make it — the site is long gone. Cuban’s mistake — and I think the mistake almost everyone makes — is that he believed that being Mavs fan would be enough incentive for some of those fans to create the content needed for the website to survive. But that’s not the right approach. For a project like Wikipedia to thrive, you need people for whom writing encyclopedia entries is fun; that is, encyclopedia fans who happen to like the Mavs. And honestly, even that isn’t enough, especially in the early stages. You need a community that thinks that the project is important.

And if you look at the early history of Wikipedia, you’ll see that’s exactly what happened. Pre-Wikipedia, the leading encyclopedia product was Microsoft Encarta. (Encarta effectively killed Britannica before Wikipedia had the chance. I’ve written about that before somewhere; if I can find it, I’ll share it on another Friday.) And the very-online world at the time didn’t like Microsoft. Microsoft was using copyright to restrict information flow, they believed, and that community preferred “copyleft” and open-source licensing for software — Linux and the like — over Microsoft Windows. Encarta was a “worst of both worlds” product to them: not only was it an effort to monetize facts and history via copyright, but it was also a Microsoft product. A small group of volunteers got together to create a free encyclopedia — free as in “free speech,” not just free as in “free beer” — and ultimately, some of them connected up with the people creating Wikipedia. They just thought it was important.

It’s a very powerful thought. I find this very relevant for this group as it provides a fair warning when it comes to thinking about the potential impact of Tools & Communities. By themselves they don't guarantee much. There are secret ingredients in terms of people (& their varied motivations) that create a way for success & enabling us to derive any benefit. That’s the secret sauce.

5. Mathematical beauty of paper size

The earliest recorded discussion of the idea comes from a 1786 letter from German academic Georg Christoph Lichtenberg to author Johann Beckmann, but there is a suggestion it might have already been a problem used in a maths exam even earlier. However, it was not until the early 20th century that Germany – and then eventually most of the rest of the world – actually standardised the idea. It is now known as ISO 216, an international standard paper size.

We’re talking about our beloved A4 size paper. If you’re up for a bit of ‘whaaattt!’ then give this post by Ben Spark a quick read.

6. London Bridge

“London bridge is down”- if you follow the news, you know what it means. This 2017 article from The Guardian describes a super elaborate plan about “a possible future ceremony”; “a future problem”; “some inevitable occasion, the timing of which, however, is quite uncertain”.

It’s a fascinating read covering details that are difficult to imagine. This plan has gone through review & improvement (and rehearsals) over the years. There is an artistic detailing to everything. We can see it executed like that now.

Everything is planned - that’s the bottom line.

7. Everything else

Some random goodness from the internet:

From Barcelona to Cairo, Photographer Trevor Trayno has captured Newsstands of the world (via Dense Discovery)

Jon Ching does wildlife artwork that has Hawaii written all over them (via Dense Discovery)

The Museum of Mario covers nostalgia from many eras. (via The Hustle)

Reuben Margolin creates beautiful Kinetic art. This Caterpillar with green stripe is a great puzzle for those who are up for some fun challenge. (via Joost Plattel)

The Holotypic Occlupanid Research Group aka HORG is a meticulously organized & structured database of plastic bread tags. (via The Hustle)

The secret number between 3 and 4 (via Joost Plattel)

What went down on wikipedia in the minutes after Queen Elizabeth’s death was announced (if you missed the post from Dan Lewis)

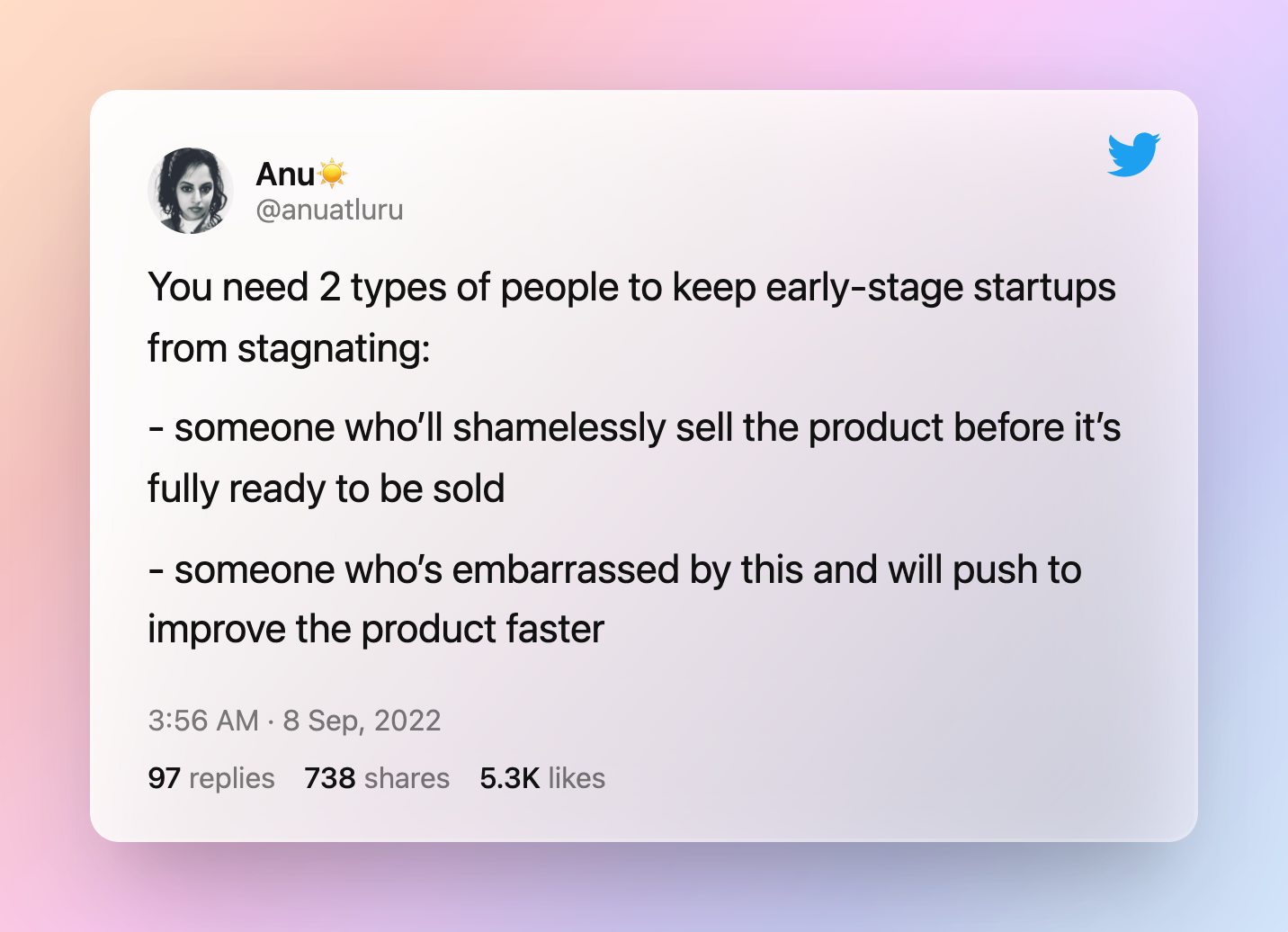

Before we sign off, here’s quick tip for those involved in early stage startups (myself included):

That's all for this week, folks!

If you enjoyed this post, show your love by commenting and liking it. I write this newsletter to share what I learnt from others. If you learnt something from this today, why not share it with a couple of your friends to continue this chain?